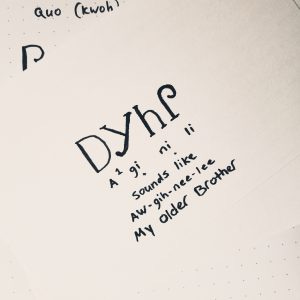

Chasing Aginili: "My Older Brother"

This is my four-month journey of how I got from using "Big Brother" to Aginili, and is an example of why learning a language instead of using "found" words is beneficial/aggravating.

I am learning Tsalagi/Cherokee over the next few years to build up a prequel novel to Fodder for Pigs. It will also enrich my current novel. At your leisure, read this full post about why I chose to do this.

I wanted to find a suitable replacement for Big Brother's "name". The term "Big Brother" has many unneeded connotations exclusive to TV show names, political statements, etc. He just needs to be a protective, though grumpy, older brother.

He will not give his actual name because he doesn't want people, particularly ones he doesn't like, to use it. That would disrespectful and sort of embarrassing for him. I began to put my feelers out for a new term that encompasses who he is and what he does.

My naive self thought I had the answer

After reading a fiction book called Walk in my Soul, about Cherokee life from the 1810s until removal from their lands, I saw the perfect word (Unginili) for my characters' older brother. This book had a particular focus on family dynamics, so I was elated.

Of course, there were some intricacies I had to explain through scenes: when the children meet their older half-brother, they discover he, according to traditional matrilineal bloodlines, is not related to them at all. They insist on calling him what translates to " my older brother". One problem with this term is technically, only a younger male sibling can call a boy "my older brother" in this way.

The children don't know better. Their blended family has strived to morph into the changing community, and only remnants of culture remain. He corrects the children when they call him unginili, but after several attempts, he finally caves and lets them have their way.

Great. Problem solved.

Nope.

For funzies, I tried to verify the word

The author of Walk in my Soul got the term from early researcher W. Gilbert, who spells it two different ways (Unginili and Unkinili), so which way is right?

Neither. It is not spellable in the syllabary, and no dictionary contains this word or term as presented. How common is it to have conflicting versions? Quite common!

According to native-languages.org, "The original tribal name of the Cherokees is Aniyunwiya (also spelled Aniyvwiya, Ahniyvwiya, Aniyuwiya, or Yunwiya.)

My brain hurts just looking at that list.

I turned to the syllabary for answers

Surely if somebody went through the trouble to define all pieces of the language, the syllabary would hold answers.

The troubling letter combo in Unginili/Unkinili is "un." The "k" vs "g" is a dialect difference based on sound and is negligible. A logical explanation is that Gilbert simply did not know how to spell the word, and relied on sounds the word made.

So what sounds does it make? What dialect differences affect the sound and thus Gilbert's spelling?

"V" makes a nasally "uh" sound. Close. I found a list of words in which this term is spelled Vginili. But what about that pesky "n" that disappeared (only "h" should do that)? Why is this version not in a reliable source?

It was not until I found the Raven Rock dictionary that I had a comprehensive guide on dialect differences in pronunciation, long and short vowels, tonal falls, etc. Incidentally, this source is the only reliable one I have found with anything similar to Unginili. The term I am looking for here is spelled Aginili and means "My older brother." "His older brother" is unili.

Why?

separating the pronoun

W. Gilbert claims that "agi" and "ungi" are both pronouns related to familial ties. I'm not sure why he chose "ungi" for this word, and my ignorance doesn't help me.

I got a simple guide, though in the Western dialect, that shows pronouns here: http://cherokeelessons.com/pdf/Cherokee%20Lessons%20978-0-557-68640-7.pdf "Agi" is "my" and "U" is "his", at least in a possessive sense for people that are alive and family. Unili for "his older brother" makes sense now, and of course, is spellable in syllables as "u-ni-li".

By that logic, does nili just mean "older brother"? Sort of. Nobody can be an older brother alone or even a friend alone. They have to belong to somebody. Furthermore, they are concepts and not a literal translation. "His younger brother" is unutsi. "Her brother" is udo. "They are brothers/his brother" is dinahlinvtsi. In fact, there is a term for every family relationship you can think of. Even uncles on each side of the family have terms that are not interchangeable.

Some words drop a sound just for simplicity in speaking

Example: according to this [Western] syllabary history sheet, "ᏧᎾᏍᏗ (tsu-na-s-di) represents the word ju:nsdi, meaning 'small.' Ns in this case is the consonant cluster that requires the following dummy vowel, a. Ns is written as ᎾᏍ /nas/. The vowel is included in the transliteration but is not pronounced in the word (ju:nsdi). (The transliterated ts represents the affricate j)."

What if the "n" really used to be "na" or some other derivative? The hunt continues.

What about the 85th and 86th syllables that were removed?

This may or may not be a factor. If the "n" in Unginili had something after it, it could be [among other things] "na" or "nah". It doesn't make my predicament any better or worse. When searching for Cherokee keyboard apps, I often encountered reviews or comments from people upset the syllable "nah" was not included in the app.

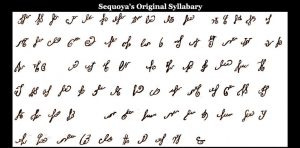

"mv" was dropped early on, and is depicted by half an English letter "G". When the Cherokee Phoenix newspaper adapted the written language for a printing press in 1827, they changed a great number of things for reproducibility in metal type, and also dropped the syllable "mv" because it was too similar in sound to another syllable. In fact, the syllabary we see today is hardly close to what George Gist/Sequoyah originally made.

This is the way Sequoyah wrote his syllables

This is the syllabary in the original order, but with adjusted shapes. "Mv" is in red.

This excerpt shows how "un" has been incorrectly used, and also explains why they dropped "mv."

Right to the source: Boudinott, Worcester, and Lowrey dissected the language for use in print.

In the 1828 August 6th edition of The Cherokee Phoenix, the Boudinott states that "un" is French, and most closely represented by syllable corresponding to "v", which is pronounced "uh." If you were to look up the French "un," you will find that it has variations based on where in France you are speaking. "Eouh" and "Aouh" are two ways of pronouncing it. The "n" is silent in both cases.

To read the rest of this newspaper edition that includes some more early language mysteries, click here: https://gahistoricnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu/lccn/sn83020866/1828-08-06/ed-1/seq-2/

Based on Boudinott's words, W. Gilbert's "unginili" can be safely re-spelled as "vginili", but the mystery remains. Why would Gilbert choose the one pronoun I haven't verified still [or ever] exists? I'm sure I am missing some very simple aspect of the language, so I'm taking it slow and trying to learn.

If you've made it this far, thank you for reading. Sometimes I think that even if I spell it correctly, most readers won't be able to pronounce it. Maybe this is all for nothing! Good thing there will be author's notes at the end of this novel!

*Note: in a previous version of this post, I stated that "nah" had been taken out of the syllabary in 1827. That is incorrect. "Mv" was removed. For a better explanation on the order of language changes, see this video by SmithsonianNMAI, featuring Roy Boney Jr. https://youtu.be/EEEu8ufwW08